The Action of Water

The action of water is often dangerous. This is something we forget when we receive it in the benign form of tap water every day.

Photo by Wendy Haakenson

I am a fluvial Geomorphologist and I love rivers. Every year, from my city home in Seattle I watch the news about winter flooding in rural areas; an increasing problem that has come with heavier rainstorms. I go out and stand on curbs watching misdirected drainage run by me on the street. I listen to the wind and the rain and think about the roof of my top-floor condo which is leaking. I hold it in as long as I can but I can’t help myself. When water moves so fast and powerfully, I am most drawn to it; so I go out to see the rivers.

January 15, 2011

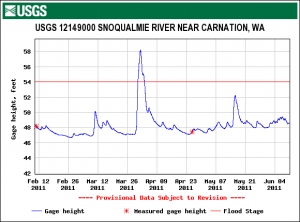

In western Washington we are in the second series of floods for the 2010-2011 water year (the period between October 1, 2010 to September 30, 2011). We have astounding valleys—the Snoqualmie, Sammamish, Snohomish, Stillaguamish—formed by glaciers, U-shaped, edged by hills or mountains with much of the valley floor largely preserved in farmland. Flooding seems to be intensifying every year. Since 1990, the frequency, depth and intensity of floods have all increased and this year appears to be setting up to be a banner year. Right now farmers, many of whom I know, are moving animals and equipment to higher ground. They’re checking United States Geological Survey (USGS) real-time streamflow data online and listening to National Weather Service and NOAA flood warnings. Towns east of Seattle, like Duvall and Fall City, have been either partially or completely cut off. People are locked into their communities defending the ground floors of their houses and rescuing others who have chosen to challenge road closure signs. Maintaining composure in light of flooded houses already once repaired and rescuing the foolhardy is difficult. It’s only January and it’s early in the winter to have had so much flooding. I picture the farmers tapping their fingers on window sills as they look out to confirm the worst.

On Saturday, January 15, when I heard the second flood of the water year had started, all I could think of was the awesome and frightening force of water; how it makes us feel small and scares us and that that awe should be teaching us something. I wanted to go to Duvall, in the Snoqualmie River Valley about 30 miles east of Seattle, with my brother and sister to eat at the Grange Café for my brother’s birthday. My brother had asked if we might not reach Duvall because of the flooding. I sent him the link to the data for the USGS water level gage. The river hadn’t reached flood crest yet and we went.

At night, the Snoqualmie Valley was an eerie, shiny lake reflecting the lights of stranded farms and fully-lit greenhouses. Some roads were already closed. We thought the river might have crested and we might not make it into town but we did. When we finished our dinner, Judy Neldam, the owner of the café, came over and said that Duvall might be cut off soon. The river was within inches of cresting. We were leaving but I wanted to stay and watch the Snoqualmie rushing by. I kept quiet. The crazy attraction to the power of the river that I secretly felt was shared by no one else—at least no one who would admit it—and we went home.

On Sunday I read on Facebook stories of the farmers I know watching the rivers rise, seeing their houses and barns flood, wondering if they would again have to leave. They elicited information on the rivers as they watched them. I wanted to help them but driving the 30-50 miles to them could just make me another human hazard so I replied to their postings saying that they are documenting the life of their community and to keep it up. That was not said without sincerity. I know they are threatened and we all need to know the dynamics of what they are living—both sides of it—and we need to think about what this means for us.

Perhaps as penance, perhaps as justification for my uncontrollable love of water and its power, since January I have been interviewing farmers about the December and January floods and am trying to create an internal balance of my feelings about the needs of those farmers and the action of water. I can’t deny that they suffer but I also can’t condemn the rivers. They are doing what they do. I hope there can be reconciliation.

Perhaps as penance, perhaps as justification for my uncontrollable love of water and its power, since January I have been interviewing farmers about the December and January floods and am trying to create an internal balance of my feelings about the needs of those farmers and the action of water. I can’t deny that they suffer but I also can’t condemn the rivers. They are doing what they do. I hope there can be reconciliation.

I have interviewed three farmers directly and talked to many others in passing since then. I managed to catch them in between floods or after a snow storm. Mostly, we talked as they worked or, in one case, had the luxury of meeting indoors when a farmer was preparing for a night meeting about flooding. I have helped sort sheep, patted a lot of dogs and cats, gotten very muddy and heard stories that were often similar but many of them unique to their particular river or particular place on that river.

Luke Woodward and Oxbow Center for Sustainable Agriculture and the Environment—January 31

Luke Woodward is the farm manager at Oxbow Center for Sustainable Agriculture and the Environment (Oxbow) on the Snoqualmie River about 5 miles south of Duvall and 35 miles east of Seattle. When I drove up to meet Luke at the barn at Oxbow he was talking on the phone. He hung up and said to me that he wouldn’t have much time because they were getting ready for another predicted storm. Tractors were out in the fields preparing them for the first spring planting since the January 16-17 floods.

Oxbow was begun in 1999 as a farm and salmon habitat restoration site through a partnership between the landowners and the non-profit Stewardship Partners. In 1999 this type of restoration was innovative. Now, the trees planted 12 years ago are thriving and Stewardship Partners has a program for “Salmon Safe” farms that certifies this and 339 other farms and vineyards throughout Washington Oregon, California and British Columbia.

Since Luke came here in 1999, there have been six major floods ranging in level from 58.79 feet to 62.21 feet. The normal level of the river is about 48 feet so that is ten feet of water that spreads over the Snoqualmie Valley. The USGS’s records show that the Snoqualmie River has reached “flood stage” (the height of the water in the river at the nearby gage in Carnation) of 54 feet fourteen out of the last eighteen years. The naming of flood intervals leads to some confusion however. It is a statistical estimate of probability rather than an established predictor of potential flooding. The term indicates that in any given year the probability of a flood that could occur once in a hundred years, for example, is one in a hundred. So the hundred-year flood can occur in any year.

Luke is fairly sure that the increased flooding he has seen since 1999 is directly connected to housing developments built since then on the valley walls of the Snoqualmie. Housing developments increase what are called “impervious surfaces”—roofs, driveways and even lawns. Water that once slowly infiltrated through the soft floor of woodlands now runs much more quickly downhill on smoother, harder surfaces. In addition, in many farmers’ opinions, Puget Sound Energy (PSE), the local electrical utility, and the Army Corps of Engineers have managed the Snoqualmie River to the detriment of the downstream inhabitants of the floodplain. PSE has been allowed by the Corps to widen the Snoqualmie River at Snoqualmie Falls in 2005 and 2009. Now, releases at Snoqualmie Falls, which is upstream from Oxbow, seem to increase the speed and volume of floods.

Regardless of how it happens, what happens when the Snoqualmie floods at the levels it has reached so often in the past twenty years is that everything: barns, animals and one hundred plus year old houses are inundated. Animals drown if not moved. Tractors and equipment are destroyed by water damage and families living on the river are in a life threatening situation. With more frequent flooding, farmers withstand crop losses more often and they are not always able to financially recover before the next big flood. This is unsustainable and a real threat to food production and the profession of farming in the Snoqualmie Valley.

Luke described the 2008 King County Task Force of farmers and local government agencies to study the problems and responses to flooding in the Snoqualmie Valley between 1990 and 2008. Among the things the Task Force reviewed were flooding patterns, damage, crop losses and the overall efficacy of regulations from the local level to the national level; one of the most salient being the issues around building “farm pads” or elevated mounds of fill to put animals and equipment on during floods. One would think farm pads would be a simple and elegant solution to decreasing loss and damage to farms during floods. However, if a large number of pads were built in any floodplain the impact during a flood would be similar to putting ice cubes in a full glass of water: flood levels would increase and overtop previous heights. So, to build a pad, a farmer needs to provide “compensatory storage”, or, in more lay terms, put a hole in the floodplain somewhere else. I wondered, in the long-term, how many farm pads could there be? There is a point at which multiple farm pads and compensatory storage in the floodplain will change what is called its “roughness” and that would change river dynamics as well. On the plus side, when the county allowed a pilot program of thirteen farm pads they found that the pads alleviated stress among farmers—an often un-discussed impact of flooding. Overall farm pads seemed like a short term solution to me. Luke said, in any case, for most farmers the price of putting a pad in is prohibitive.

Federal, state and county regulations seemed to weigh on Luke’s mind quite a bit. He showed me the agricultural building they had constructed in 2005. At that time farm pads and raised buildings weren’t allowed and they built the structure in compliance with county zoning codes on the floodplain. Since then, as a result of much higher subsequent floods, he has had to raise all of their storage off the floors at great expense. He is frustrated that had they built in 2008 after codes changed, they could have saved the thousands of dollars that it took to retrofit the

Federal, state and county regulations seemed to weigh on Luke’s mind quite a bit. He showed me the agricultural building they had constructed in 2005. At that time farm pads and raised buildings weren’t allowed and they built the structure in compliance with county zoning codes on the floodplain. Since then, as a result of much higher subsequent floods, he has had to raise all of their storage off the floors at great expense. He is frustrated that had they built in 2008 after codes changed, they could have saved the thousands of dollars that it took to retrofit the

Luke told me about a law that has had serious impacts on all farmers since Hurricane Katrina. In Katrina, a lot of the water that broke levees flooded into industrial areas. When it washed back into residential areas and farmland it brought a toxic stew of industrial contaminants with it. As a result, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) passed regulations against selling foods from areas that had been flooded—nationwide. Since most farmers in the Snoqualmie Valley grow root crops and some hardy greens like collards during the winter, when it most often floods, this has cut into their income.

Luke gave me plenty to think about. My primary response was surprise. I hadn’t realized the extent to which the Snoqualmie is a controlled river: with flows manipulated at Snoqualmie Falls and increasing regulations of the floodplain. The Snoqualmie, to paraphrase Aldo Leopold, is a river “…confused by so much advice.”[1] It’s still beautiful but maintaining that beauty as well as a balance among farmers, people living in the hills, Puget Sound Energy and wild fish is not an easy zero-sum equation. To grow food, do it using organic practices and sustain this farm, Luke is pulling a lot of threads in an intricate and fraying weave. Pull too far in one direction and the fabric of the farm is altered. The interplay between this farmer and this natural system is a quest for sustenance in the face of powerful dynamics. The limits of what can be withdrawn as produce will be met at some point but when?

Linda Neunzig Herding and Sorting Sheep—February 13, 2011

Linda Neunzig is the Agricultural Coordinator for Snohomish County; one county directly north of King County, where Seattle is located. She is a Chef in the Slow Food community, a highly capable horsewoman, a Certified Veterinary Tech in California and Washington and a sheep and cattle farmer.

Ninety Farms is about 40 miles northeast of Seattle, a half mile from the banks and approximately 5 feet above the floodplain of the Stillaguamish River. This is a different drainage basin with different weather than the Snoqualmie. The “Stilly”, as locals call it, is not dammed upstream nor is it as susceptible to snowmelt flooding as the Snoqualmie. Flooding at Ninety Farms is mostly a result of heavy rain. Floodwaters this year brought a fine silt that covers the ground where Linda grows grass and she is going to have to drag and re-seed the pastures so that the roots can breathe and grass will grow thick again. She is culling her herd because this year there will be less food for the sheep. Reducing feed reduces the number of lambs she can sell to her customers and thus her income—putting a dent in one of the few local sources of naturally raised lamb as well.

On December 12, 2010 Linda’s house and barns were flooded with four feet of water. She and a friend moved the 300 or so sheep, 3 horses and a multitude of cats and dogs to higher ground on his farm. While a farm pad may have helped her avoid the moving, she says it wouldn’t have changed the cleanup. It took three weeks and the volunteer help of many friends to clean up and bring the sheep back. They were lambing when the flooding started and they were still lambing four months later.

When I showed up early that Sunday morning, Linda was away getting fuel for her tractor. As soon as she got back she started working. She put diesel in the tractor, started preparing the barns for cleaning and let the sheep out of their main barn to the pasture. I asked her questions as she worked but mostly followed along watching what she did and let her comment.

We started working by moving new lambs. A mother had given birth to two lambs in the last hour. Their umbilical cords were dangling and the mother’s milk bag has a streak of blood from the uterus. We walked them over to the horse barn, set them up so that the mother could bond with them and then took the three horses to their pasture. All the while we were followed by a gaggle of cats and dogs. Tillie, the Corgi Linda uses to herd, was constantly at her heels. One young cat inserted himself into everything she did.

As Linda cleaned the barns and yard with the tractor, I walked down the road to the Stilly to take pictures. It’s a beautiful river with gravel bars on alternating sides of each meander and piles of debris—trees and logs—piled on the banks.

On my way back I saw a farmer whom Linda had told me would be coming to buy pregnant ewes. Linda had set aside about 23 and now had to identify them by age for the buyer. I was recruited to make a list on a receipt pad: 1 yr, 2yr, 3yr, 4yr and full mouth and put hash marks by each as she looked in their mouths and checked to make sure each has two-bag udders. She then released pregnant ones one-by-one to a fenced off part of the barn from the pen in the back where they had been held. One, she called “Coyote” wasn’t supposed to be in there. This one had been attacked by a Coyote when it was young. Its throat was so torn that when it swallowed food it came out of the side of its neck. Linda said, “We fixed it. We didn’t know if she would recover but she’s fine now.” After a while I realized that when Linda said “we” it was mostly an understated way of saying she did something. As she checked the sheep “Coyote” got out. Linda said, "Oh you can have her for free in case there are some that are not carrying babies." In the process of selecting she added in another two just in case.

When she was almost done Linda asked me to count the sheep she had already released. I needed to ascertain whether twenty or nineteen sheep had already been released. The penned sheep moved constantly but together; head to tail, head to head, tail to head. I tried to count by head but they moved up and down, disappearing behind and over each other. When Tillie got them fairly tightly into a corner they still shifted like jello. Finally, I determined that there were twenty. The idea that counting sheep is restful is a complete misrepresentation of anything that happens. No more images of the fluffy white ruminants jumping over logs for me.

When the trailerful of sheep was gone, we moved out to the fields to bring back the herd and sort about 20 more for butchering on the coming Thursday. Linda went out ahead of me. I kept my distance watching what she did. Linda and Tillie actualized a lot of the imagined herding I did when I owned a Border Collie. They turned the sheep towards the buildings and herded them together with an occasional bark and arm waving. They passed me at a distance as I moved further out past them to look at a large nest in the poplars along the river.

Linda said, “OK, that’s good. Let’s put these guys back in the field.” We moved the portable fence and she lead the main group out with Tillie. I stood guard to keep the sheep from going back into the barn. To the right I saw sheep coming from the back pen down a chute. I was watching them and thinking there was a gate blocking the chute but all at once they ran out of the barn and joined the main group! I ran out to Linda just as she was ready to open the gate and yelled to her that they got out. “What? Dammit!” She stopped, silent, then turned around and said, “OK we have to do it again.”

This time in the barn the herd was quieter, panting more, moving more slowly. Linda was quieter too. In another 15 minutes or so the sheep to be butchered were penned again. I watched for them to escape. They rammed the pen in the same spot but no luck. The main herd was let go out to the fields.

At one point in the sheep moving and gate opening I told Linda that it reminded me of the dots and squares game I used to play as a kid where you put dots on a paper in a grid then compete with someone to close the squares. It seems that at some point in the past this pencil and paper game would be good training for what we had been doing because if you don’t close the square you lose. Is it just coincidence or is there some agricultural heritage being passed down by this game?

I was ready to wrap up the day and Linda had been invited to dinner by a chef friend so I wanted to give her time to get ready. A couple of times during the day she had stopped and looked at me with her intense blue eyes and said, “You must think I’m crazy.” What I was thinking was not that she was crazy but how incompetent I was as I watched her move and guide and handle the cats and horses, lambs and dogs and tractor while answering the phone and the occasional question from me. She didn’t lose a beat moving quietly from one thing to another. Perhaps when no one is around she might get frustrated and show it but she had only shown that once in five hours of steady work.

I don’t believe Linda would or could do this work unless she was deeply connected to the rhythms, the air, the water, the animals and the land. It all matches a power within her that needs to be matched—that visceral connection with the natural world that some people can’t ignore. For her the river either makes this possible or impossible and I saw her on a day when she was not fighting the river. It was incredibly peaceful just to watch her manage her piece of the universe.

This peace ultimately was transitory. While I was there I asked Linda about a nest out in a windrow of poplars along the river beyond the pasture. She asserted that it was a hawk’s nest but I wasn’t so sure. Later in the winter, between the second and third floods, she had to confront bald eagles and coyotes taking lambs. The eagles were flying into her barn to get them. To ward off the coyotes, Linda purchased three Llamas; but for the eagles she had no solutions. In addition she suffered through two snowstorms that didn’t affect farmers further south. The storms were late in the year and that was difficult enough but on the question of why the eagles were so aggressive, it seems that the cumulative systemic impacts of such a harsh winter had affected food sources for the wild animals. Her challenges with eagles and coyotes continued through the Spring.

Erick and Wendy Haakenson, Jubilee Farm, Snoqualmie River—February 14

Jubilee Farm is on the west side of the Snoqualmie Valley about 10 miles south of the Oxbow Center. When I visited many of the fields were still wet from the January flood.

Erick seemed somewhat inured to the flooding as a fact of life he has dealt with for years. He and Wendy lived for five years in a manufactured home across the road from the new house. On November 7th of 2006, in the middle of the night, their home was inundated by floodwaters that rose four feet up the walls. That older home has since been raised and become the residence for farm hands.

Erick’s concerns with the flooding were not completely with the erratic and unpredictable patterns of the recent past but with the ultimate impacts of climate change and the future scarcity of water. The signal through the noise in hydrologic disruption is the steady rise in temperature that has been occurring for 50 to 100 years depending on what sources you cite. Glaciers have been shrinking more than growing for at least 100 years. If temperatures do continue to rise, the predicted scenario is that water now stored in the mountains in snow and glaciers will all be released during the winter instead of during the summer growing season. This is a problem for all of western North America from British Columbia to southern California where metropolitan water systems are designed around winter storage in snow and ice reservoirs. An adaptive approach that Erick considers a serious one is the idea of building small reservoirs in the mountains to supply winter storage and summer water for farming and water supplies. This idea is so fraught with repercussions on potential environmental impacts that Erick acknowledges he has to qualify any discussion of it very carefully.

Since 2009 Erick and the Snoqualmie Valley Preservation Alliance (SVPA) have been working on a lawsuit against US Army Corps of Engineers in relation to the widening at Snoqualmie Falls that Luke had mentioned. In the permit process, the EIS reported a determination of non-significance, or DNS, for downstream impacts. Erick and other farmers are appealing this decision in Federal court. PSE petitioned the court of be included as co-defendants, and that petition was granted. The SVPA argues that no downstream impact studies were done to determine what the impact of up-river flood alleviation would be and no public review was allowed. They are also pointing out that this project is not a good solution for native fish. Increased flows over Snoqualmie Falls seem to increase downstream flow velocity significantly during floods. This might serve the upper valley well by reducing flood heights but increased downstream speed and flows will potentially cut into stream banks, flood more fields and also scour the river bottom eradicating salmon spawning beds.

Erick is an eloquent speaker, deeply philosophical and clearly connected to the piece of land he’s sees himself as being privileged to steward. He and Wendy have a somewhat unique Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) share program in which people come out to Jubilee Farm to pick up their food. This does not, like many CSAs, defray the travel cost but intentionally brings people to the farm so that they can have a direct connection to the production of their food. Their practices emulate a basic tenet of the local food movement of the noted local food activists in Seattle, Viki Sonntag, who often says,

“It’s about relationships.” [2]

What is the Future we can see?

Erick and the other farmers welcomed me back at any time and I went back to see Erick and Luke. In March and May the Snoqualmie River rose again delaying planting. An unusually cold Spring further delayed planting as far out as June for some farmers. Fields were still muddy in some spots when I was there on June 4. I am in touch with Linda by email and the last time she posted on Facebook, she had 150 lambs sequestered in her barn to protect them from the eagles.

I have reflected a great deal on the implications that the experiences of these three farmers have for the food system and for the world. The thoughts from Luke about the current control of the Snoqualmie were a caution to me, the example of Linda and her absolute fierceness in engaging with every piece of the natural world that she can were an inspiration, and the small hint at what could be if we build the small reservoirs in the Cascades that Erick talked about lead me to a vision of a future that I and many others try to avoid thinking about.

The current strength of the local food movement throughout the US has increased the appreciation of farms and farmers. Many in Seattle hope that the city and region can be sustained on local food in the future; with much of it being produced in the Snoqualmie Valley. But the climate and the dynamics of rivers are changing. We are dealing with much more variable variability and the making of any predictions over the long-term is something we should be cautious about.

I may be wrong in many people’s eyes to be excited by the powers that natural systems have but our loss of respect for those systems is pretty incontrovertible. We are living the reality humans created. Population, pollution or just the now-unstable, varying patterns of precipitation around the earth are challenging us everywhere and I don’t think we’re able to say that people will always win. While I also hope that we can create a local food system I wonder how that will actually happen. We want healthy, locally grown for everyone. We want high quality farmland to be preserved for both practical and aesthetic reasons. We all, to some degree, idolize Wendell Berry and envision ourselves being connected to place like he and Aldo Leopold.

I felt myself being niggled at the ear by devils. A specific point in all of these interviews that fed my devils was Erick’s discussion about the reservoirs in the mountains. If we honestly think about world population as projected on the exponential trajectory it’s now on, there will be an estimated nine billion people on earth in 2050. This presents challenges I’m afraid most food activists are unwilling or unable to visualize or confront. I can’t even grasp the real possibility of it myself and I wonder how many of us can.

In 2050 my son could be a grandfather. Given population growth and the technical development and environmental destruction that have occurred since I was a four-year-old child playing by streams in New England woods, I think in that future, if we have built a few small reservoirs such as those Erick mentioned, it would be a minor alteration among many more technical. And, while we love the idyll of returning to a pastoral life, it seems more likely to me that current responses to food scarcity will be on the path of primarily infrastructural solutions like those reservoirs. Water conserving and permaculture farming practices will help but simply based on the potential demand for food, they may not be enough.

Of most concern to me is that this future won’t include ways to meet the real human need for a raw connection to the natural world. I can’t see the world where we give this up and I refuse to conclude that I am an evolutionary throwback with too many atavistic urges. I would rather say that I represent the true realities of human existence and that Luke, Linda, Erick and all those who yearn to grow their own food, live on a farm or just wander in the woods do as well.

There are those who might reply that evolution in response to increased population and immense technological change will lead to the diminishment of atavistic urges in the favor of a species much more accommodating of things like brain implanted communication devices and real time connections to almost everywhere in the world. I don’t want to buy into that idea but when I read an article in Wired Magazine Joel Johnson wrote something that seems to support it,

“…I believe that humankind made a subconscious collective bargain at the dawn of the industrial age to trade the resources of our planet for the chance to escape it. We live in the transitional age between that decision and its conclusion.”[3]

Many of us in the developed world are indeed escaping to the colorful electronic worlds and the internet. I participate too, often like it, and wonder at it but I don’t think that obviates my real human nature. Despite the long-ago description by Aristotle of a world made of atoms and the 18th century theorists who changed views of the world to see it as a part of a mechanical universe, I don’t think there has ever been a time when people did not search out the unreconstructed natural world nor do I believe there ever will be so I stand my ground.

These three farmers are a small cross section of those in Western Washington. That they and others like them are surviving at all is remarkable but when people choose to make their living in the path of the constantly changing dynamics of water and other natural systems they have to be instilled with qualities that many don’t have: incredible perseverance and the ability to work almost continuously in heat, cold and wet. And they also fulfill the aspirations of many of us who want to be back on land, touching it, breathing in the living smell of earth; and they will not give those things up. I won’t either!

I worry about the farmers. I worry about food. I worry about the once-again threat of extinction of the bald eagles that play outside my window. When the rivers come up, my blood roils and in my heart meanders to those places where the powerful water is flowing. I must go there and stand by the river to touch it and remember who I really am. I can work with these forces within me. I trust the farmers I know can too. For those in doubt or in need of direction about what we should do, I say first, “Go find your river.” I’ll be standing by mine and from those places; be they metaphorical or real, we can all look forward and back and envision the world in all its complexity as a place where we create something better for not just us and our children but every living ounce of it.